From LSD to Ayn Rand to Satanism, the roots of Marvel’s latest superstar are a tangle of the American unconscious. John Naughton elevates to the astral plane to investigate.

“Open Your Mind,” advises the trailer to the forthcoming movie of Doctor Strange. “Change Your Reality”, it adds, as cityscapes fold in on one another Inception-style and the titular Marvel comic-book hero – made flesh in the form of Benedict Cumberbatch – opens the doors of perception and inspects his new, deceptively spacious surroundings.

Though he’s had to bide his time patiently to take his place on the big screen in the new Marvel Comics Universe, behind the likes of Iron Man, The Hulk, Captain America and the rest, Doctor Strange arrives on the big screen this month and expectations are, well, high.

Because from his very earliest appearances in July 1963 in the pages of Strange Tales #110, Doctor Strange, with his cosmic wanderings across astral planes, protecting Earth from dark forces often only with his mind, has been intimately linked to LSD and the counterculture.

Since that time, he has been reimagined successfully by writers such as Roger Stern and most recently, Brian K. Vaughan in the excellent one-shot, The Oath. But most comic book aficionados would agree that there have been two iterations of the Sorcerer Supreme that stand out above the rest. The first was the original run, drawn by his creator, the enigmatic, reclusive, comic book genius, Steve Ditko and the second was during an intense period of creativity at Marvel in the early 70s when writer Steve Englehart and artist Frank Brunner took over his story.

Both runs were seen to be influenced by and endorsing the use of mind-expanding drugs like lysergic acid. Yet Steve Ditko created his character without any pharmaceutical assistance whatsoever while Steve Englehart and Frank Brunner? Well, yes, they took drugs. Lots of drugs.

Doctor Strange was an enabler of the hippy imagination, a cosmic prophet of the psychedelic counterculture and an inspiration to a generation as they discovered LSD. And, strangely enough, he didn’t really mean to do any of this.

Though he would journey across astral planes and parallel worlds the like of which had never been seen in comic books before, Dr Stephen Strange owes his existence to two earthbound Acts of God. The first was the Johnstown Flood of 1889 which killed over 2,200 people in the Pennsylvanian town and, with a pressing need for fresh bodies to replace the dead workers, led to a wave of Austrian and Polish immigration, including a family by the name of Ditko. The second occurred on August 18, 1955 when Hurricane Diane swept through Connecticut, killing hundreds in its wake and destroying the premises of comic publisher, Charlton, where struggling artist, Steve Ditko – not long recovered from a life-threatening bout of TB – was earning a meagre living.

With the publishers (temporarily) out of business, Ditko took his portfolio into Manhattan to Atlas (soon to be Marvel) Comics, where he met the company’s creative and commercial powerhouse, Stan Lee and initiated one of the most fruitful partnerships in comic book history. From the start it never ran true; Lee had to lay off the entire workforce in 1957. But when he was tentatively looking to rebuild the company a year later, Lee’s first two hires were Jack Kirby – who would go on to co-create the Fantastic Four, the X-Men and the Hulk – and Ditko, who at that time was sharing a studio with Eric Stanton, a Manhattan fetish artist of some note.

By 1962, Ditko was providing the art and shaping the character and costume of a superhero who was dealing with his foes with an altogether more acceptable form of bondage. But while Spider-Man was a combination of the talents of Kirby, Lee and Ditko, Marvel’s next major hit, Doctor Strange was more of a Ditko creation. This was acknowledged by Lee himself – in a manner as comically lukewarm as David St Hubbins’ introduction to ‘Jazz Odyssey’ – ahead of the character’s debut.

“Well, we have a new character in the works for Strange Tales, just a five-page filler named Doctor Strange,” Lee wrote in the fanzine, The Comic Reader #16 of February 23, 1963. “Steve Ditko is gonna draw him. It has sort of a black magic theme. The first story is nothing great, but perhaps we can make something of him. Twas Steve’s idea.”

Steve’s idea debuted in Strange Tales #110 in July 1963 and told the story of egomaniacal surgeon Dr Stephen Strange, obsessed with personal glory and earthly possessions, who, as a result of a car crash, loses the use of his hands. In search of a cure, he travels to the Himalayas where he meets mystic guru The Ancient One and undergoes a Damascene conversion. Committing to being The Ancient One’s disciple, he successfully applies for the niche position of Sorcerer Supreme, defender of the inhabitants of the Earth against black magic as practised by the likes of Baron Mordo and the Dread Dormammu.

- Doctor Strange then (in his first appearance, 1963) and in 2016.

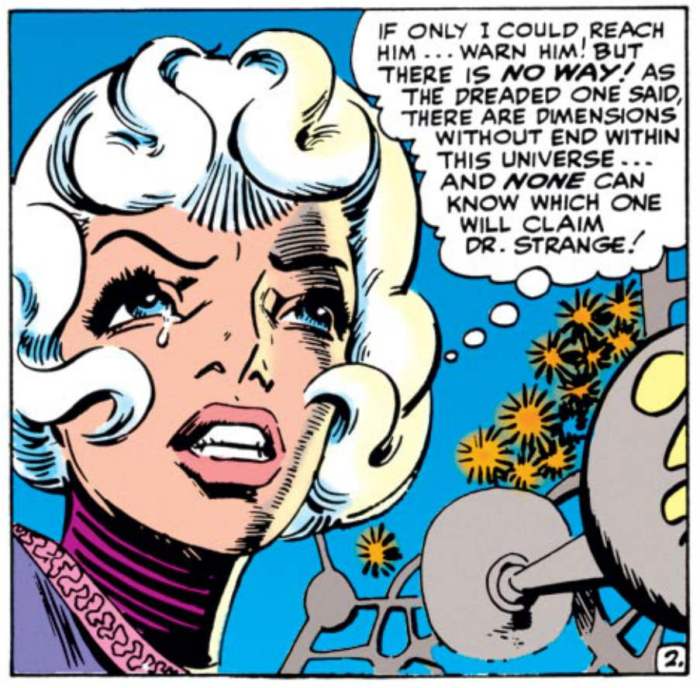

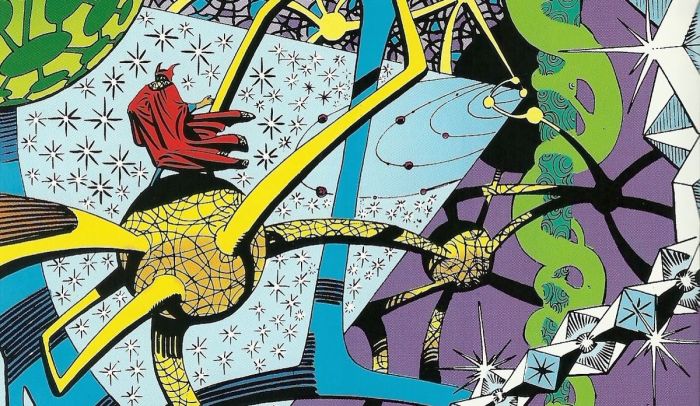

For writer, Steve Engelhart, who was a teenage fan when the character debuted, Ditko’s work remains definitive. “Ditko had that really cramped, dark, angular style which for Doctor Strange was perfect,” he explains. “In the original Doctor Strange, he’s got that really sharp face and the Fu Manchu moustache, very slant-eyed, very dark, very distinctive. Then there are the worlds he created with things opening up and stairways coming out of holes, that was unique. Nobody had created a world that looked like that. To this day, anyone who draws Doctor Strange is going to try to replicate that; nobody’s reinventing Doctor Strange visually.”

Steve Ditko’s artistic style, refined and honed over thousands of pages is a unique and beloved one and reflects his keen attention to the styles of other artists stretching back to the time when he learnt his trade at New York’s Cartoonists and Illustrator’s School under Jerry Robinson, co-creator of The Joker and Robin from Batman. But the key influence on Ditko’s work and art for over two thirds of his life has been not an artist, but a novelist, the eccentric and wildly controversial pioneer of Objectivism, Ayn Rand.

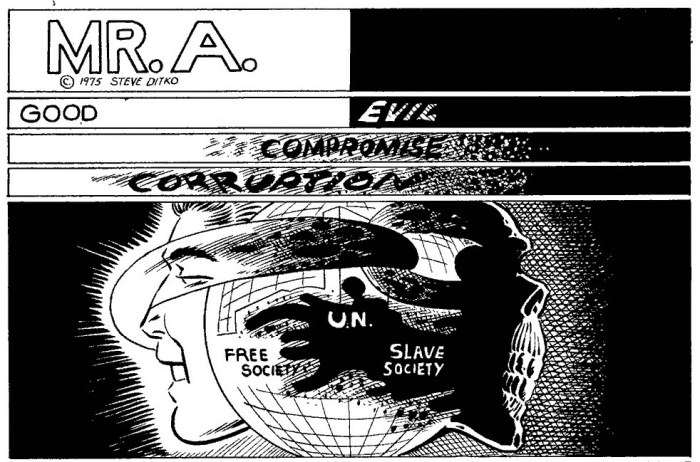

With her fourth and final novel, Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957 and never subsequently out of print, Rand put the final touches to a philosophy which takes as its ideal the man who lives by his own effort and where the moral purpose of life is the rational pursuit of one’s own happiness. Only laissez-faire capitalism can protect the individual’s freedoms in a world of simple, but defining choices, where black is black, white is white and altruism – along with any variety of socialism – is strictly off-limits.

Ironically, given their subsequent rift, Ditko’s interest in Objectivism began when Lee showed him a copy of Atlas Shrugged around 1960. Rand’s concepts of how a hero should never compromise his ideals fed directly into his creation of Doctor Strange, where it collided with a range of different interests.

“There’s a proto version of Doctor Strange and he’s called Doctor Droom,” explains comic book journalist and historian, Colin Smith. “Droom was created in 1961 by Lee, Kirby and Ditko and he only lasted for five issues. In the first story, Doctor Droom is so suffused with magical power that his eyes become Oriental and he develops a Fu Manchu beard. He came back as Doctor Druid because his original name was too similar to Doctor Doom.”

Ditko was ideally placed to develop Doctor Strange as he was already vastly experienced in producing similar stories. “Ditko’s been doing short stories of 6-8 pages for almost a decade by this point,” Smith expands. “He’s been churning out science fiction shockers, horror shockers and all of the tropes that you see in Doctor Strange, to one degree or another can be traced back to these. A haunted house turns out to be an alien. Early Doctor Strange stories are very clearly horror stories.”

Working with Lee, but giving full rein to his creative inspiration, Ditko delivered a run of remarkable Doctor Strange stories which established the look and direction of the character. “Ditko was a lightning rod,” continues Smith, “and he was saying, You know what, I’m really interested in ghost stories, I’m really interested in Ayn Rand and I’m bloody well going to use this blank canvas and I’m going to fuse them.”

“You don’t have to take drugs to write fantasy,” adds Steve Englehart. “It’s just what’s in your brain, no matter how it got there. Ditko had always done weird stuff so he was perfect for Doctor Strange , and the original Ditko stuff is still the archetype for everything on the book. The worlds that he created were unique – and Stan could write anything.”

Although 1963 was the year that sex was invented, it was still fully two years before The Beatles took acid for the first time. Yet Doctor Strange was soon a source of inspiration for early adopters of the counterculture lifestyle. Ditko’s wondrous realisations of fantastic realms of the imagination provided the visual architecture for the LSD generation.

In his work of 1968, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe recalls Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest and notable member of the Merry Pranksters, aboard the famous Magic Bus, spreading the gospel of LSD across the States in 1964. “Kesey is young, serene and his face is lineless and round and smooth as a baby’s as he sits for hours on end reading comic books, absorbed in the plunging purple Steve Ditko shadows of Doctor Strange,” wrote Wolfe.

Where Kesey led, others soon followed and by 1967, Doctor Strange’s influence was becoming embedded in the counterculture. Posters for the first shows at Bill Graham’s Filmore West Ballroom borrowed liberally from Marvel comics generally, and the Sorcerer Supreme specifically.

His influence reached across the Atlantic as well with Pink Floyd, perhaps unsurprisingly, in the vanguard. Take a close look – as indeed would have been compulsory at the time – at the cover of Pink Floyd’s 1967 album, ‘Saucerful Of Secrets’ and on the right is the unmistakable image of Doctor Strange taken from Strange Tales #158 staring across at The Living Tribunal.

Speaking in 2010, Storm Thorgerson, co-creator of many of the band’s album covers, said, “The cover is an attempt to represent things that the band was interested in, collectively and individually, presented in a manner that was commensurate with the music. Swirly, blurred edges into red astrology, Doctor Strange images merging into images, a million miles away from certain pharmaceutical experiences. Beginning with ‘Saucerful…’, they were starting to experiment with more extended pieces and the music would cascade and change from thing into thing.”

Confirming their interest in the Marvel character, Pink Floyd’s song ‘Cymbaline’ – released on the soundtrack to Barbet Schroeder’s 1969 tale of Ibizan heroin addiction More and referencing another touchstone of the psychedelic experience, ‘Alice In Wonderland’ – contains the lyric, “You hear the thunder of the train/Suddenly it strikes you/That they’re moving into range/And Doctor Strange is always changing size.”

Doctor Strange’s presence in the creative ether receives further endorsement in Marc Bolan’s ‘Mambo Sun’ where, as well as alarmingly assuring his intended that he has “wild knees”, he then insists, “I’m Doctor Strange for you.” Throw in his presence on a couple of Al Stewart album sleeves and, of course, the name choice of experimental Irish folkies Doctor Strangely Strange, and it’s clear that the mystic medic was as reliable a source of inspiration to psychedelic creatives as the generously proportioned female backside is to rap.

This state of affairs could only have added to the anger of Doctor Strange’s straight-edge creator, Steve Ditko, who, by the time Pink Floyd and co were referencing his creation, had long since severed his relationship with Stan Lee and Marvel Comics.

As the 60s progressed and McCarthyism became a more distant memory, a spirit of liberalism took hold in America and this was reflected at Marvel Comics. But not by Steve Ditko.

“The reason he stopped doing Spider-Man,” recalls Steve Englehart, “was that he wanted to draw teenagers wearing ties. That wasn’t the way teenagers looked any more. He was a little out of his time in that regard and they needed someone a little hipper.”

One of Ditko’s last Spider-Man strips saw Peter Parker scorning a group of student protestors. It mirrored a growing political and personal rift between Ditko and Lee.

“In the early Marvel days, Stan Lee was an absolutely foaming red-baiter,” explains Colin Smith. “As the 60s progress, Lee begins to turn towards a New York, liberal, Jewish humanism, which I suspect was what he always really believed. But as this happens, Ditko is moving towards libertarianism while Kirby is really pushing radical ideas, like Black Panther, a black superhero. This creates this fantastic conflict that you see in those later Spider-Man issues.”

Stan Lee was no longer the foaming red-baiter of his early days. Ditko’s libertarianism fed into his unhappiness at the lack of rewards at Marvel.

Adding to the tension at the Madison Avenue offices of Marvel was the fact that Lee was management (and family, as his cousin Jean was the wife of overall boss, Martin Goodman) while Ditko and Kirby were hired hands, with no entitlement to share from the profits of the company or their comic book creations.

“Lee and Ditko worked brilliantly together,” continues Smith. “But they weren’t chums, they weren’t political allies and as Ditko’s libertarianism fed into his unhappiness at the lack of rewards at Marvel, you get a kind of feedback loop that helps to separate him from Lee.”

Eventually Ditko quit. The tension inherent in producing stellar work for his bosses and seeing no reward – in direct contradiction of a central tenet of Objectivism that a creator should profit from his creations – was just too much. In short; he was being ripped off and he couldn’t take it any more.

It’s a question that runs through almost every collaborative artform and probably began with a dispute over the split on the Lascaux cave paintings box office: who gets exploited, who does the exploiting. In the case of Marvel, it led to Jack Kirby’s departure shortly after Ditko. But whereas Kirby’s estate successfully sued Marvel for lost millions, Ditko walked away and has never sought legal counsel.

“Ditko would say ‘I signed it’,” asserts Colin Smith. “‘I signed that piece of paper. I knew I was doing it. If I didn’t know I was doing it, I would fight back. But I did know it.’ This is absolutely intrinsic to libertarianism or Objectivism. He is a man of his word. He owns his decision. I’m not in the least critical of the Kirby family, I think they’re absolutely right to fight those lousy bastards who did him over. But Ditko steps outside this. The value of something to Ditko is in the truth it expresses. He’s got some very strange attitudes, but credit to him, he’s lived his life by them.”

Ditko subsequently produced strips of an increasingly difficult, intense nature such as The Question and Mr A which reflected his growing Objectivist convictions. Separated from Lee’s excellent commercial instincts and editorial expertise, they were not for the faint of heart. Think Scott Walker’s solo stuff.

As Ditko walked off into the sunset (he would subsequently return to Marvel, but never collaborated with Lee again) his irritation at loss of profits would have been compounded by the popularity of his creation among the counterculture.

“The counterculture were really quick to jump on to Marvel,” confirms Smith. “It loved Ditko, so he’s being read by the proto-hippies on the West Coast from the very earliest days.”

Quoted in Blake Bell’s The World Of Steve Ditko, Cat Yronwode, a Ditko scholar and sometime collaborator, recalls the San Francisco scene of the time. “There was this one issue of Spider-Man in which Aunt May needs this drug called ISO 36. Everyone I knew said it was code for LSD 25. Then there’s the Spider-Man issue with Mysterio where there are all the hallucinations and hypnotic delusions… My friends and I out there in West Berkeley were like, Oh my God! Steve Ditko smokes grass and takes acid!”

“You can bet your soul that he has never taken acid,” laughs Colin Smith. “What’s more, there’s a fundamental antipathy between libertarianism and any sort of group. Then the idea that that group is one dedicated to self-exploration only makes it worse. Suddenly, with Doctor Strange he became the prophet of something which he must have loathed.”

By the time of Doctor Strange’s second great period, much had changed at Marvel. “It’s another golden age,” asserts Colin Smith. “The real danger to the superhero comic was always success. It was always at its best when it was an utter commercial failure and nobody bothered the creatives. By 1973 at Marvel, there’s very little editorial control and sales are plummeting and what you get is this wonderful chaos. There’s no central control. They can’t fill the pages. They’ve got absurdly mad systems. According to Gerry Conway [creator of The Punisher], part of Marvel’s office at this time was run by Satanists. There was a practising coven in the editorial office.”

But alongside the coven there was talent. Artist Frank Brunner teamed up with writer Steve Englehart and set about reinvigorating Doctor Strange. Englehart had already worked the oracle with Captain America, saving him from near cancellation (and in the process, obliterating the Captain’s post-war anti-communist antics by writing him off as an imposter). Within three months, he was Marvel’s most best-selling book.

Englehart set about doing the same for Doctor Strange.

“When I took over Doctor Strange, I thought this guy is supposed to be smarter than anyone, including me,” recalls Englehart. “He’s meant to know all the secrets that nobody else knows. I made my best attempts to try to be smarter than I was, to try to write the Sorcerer Supreme.”

As part of his brief, Englehart decided to investigate the magical terrain occupied by Doctor Strange. “I read up on Kaballah and Tarot and the Western approach to these things trying to get the mindset right for the character and the vibe right for the series,” he remembers. “I got pretty deeply into it and it’s something that I’ve paid attention to ever since. I learned astrology and all that kind of stuff. Star-Lord, now starring in Guardians of the Galaxy [played by Chris Pratt], originally started as an astrological concept in my mind. I was learning stuff so I was playing with it.”

Englehart was also experimenting vigorously with LSD. His and Brunner’s creative process involved a monthly dinner together where they would drop LSD and discuss Doctor Strange plots into the small hours. This was supplemented by frequent nocturnal journeys around the more dangerous parts of Manhattan, of which there many, again under the influence of acid. One night they climbed up the statues of The Four Continents in front of what was the US Customs House in Lower Manhattan, and cooked up a Doctor Stange story where each statue was transformed into thousands of living soldiers, ready to do battle against Atlantean invaders.

“I’ve never been coy about LSD,” Englehart laughs. “It was the 70s and I enjoyed my time in the 70s. It’s the old thing about where do you get your ideas. Well, you get your ideas from the entire contents of your brain and the more places you go in your brain, the more possibilities. Whatever drugs might have done, they didn’t just feed into Doctor Strange, they fed into everything I wrote. It just gave me more freedom to imagine what could happen.”

For the Bicentennial celebrations of 1976, Englehart had Doctor Strange journey back to the signing of the Declaration of Independence and investigate the occult influences upon it. “Most of the signatories were Masons,” explains Englehart. “So there is a theory that the whole thing was Occult-orchestrated. So for Doctor Strange I was perfectly happy to go with that.”

Looking back now, however, Englehart admits that the storyline whch gave him greatest pleasure was one in which Doctor Strange meets a sorcerer called Sise-Neg (Genesis backwards) and travels back in time with him as he gains power and becomes God.

“There wasn’t really a downtime for me with that series,” recalls Englehart. “I took it over mid-stride, they were in the middle of an adventure and we wrapped that up, then did the God thing, then later I did Death and Life. Everything was like a big concept.”

The story goes that Stan Lee was getting cold feet about the idea of Doctor Strange meeting God until he received a letter from a Texan pastor singing the praises of the strip and the positive effect it was having upon his flock. A letter written by Steve Englehart.

“There was a saying around Marvel that Stan Lee could be deluged with a postcard. So being young and creative, we thought, Let’s send him a letter.…”

“We had heard that Stan was unhappy or uncertain about the whole God storyline,” Englehart says with a smile. “There was a saying around the Marvel bullpen that Stan could be ‘deluged with a postcard’. So being young and creative, we thought, Let’s send him a letter. I lived in California so I was going to have to transfer planes in Texas when I was going home to my family. So I thought I’ll write this letter as a pastor and say I enjoyed that story. Whether that deluged Stan, we don’t know but the problem was solved. We were really trying to go new places every time so we really didn’t want anyone telling us we couldn’t.”

Like Ditko, it all ended messily for Englehart and his generation of Marvel storytellers. However, Englehart has gone on to enjoy success across a number of different media and seems at ease with his past, while belatedly realising it was a Golden Age for comic books. Moreover, he views the forthcoming Doctor Strange film with keen anticipation.

“Marvel has proven to me that they know how to do this stuff now,” he reasons. “They’ve gone from saying, ‘We are going to take our best shot at doing a film for superhero people’ to ‘We’re going to do a film’. The latest movies have been really solid movies without a lot of nodding to the fanboys, but still hitting all those notes.”

Colin Smith remains more sceptical about the recent glut of superhero movies, but his love of the comic book format and Doctor Strange’s place within it remains undimmed.

“What’s fascinating about Strange is what’s brilliant about the superhero when it’s done well,” he enthuses. “The superhero is a fantastic, unstable challenging locus for taking a heroic type and then loading it up with cultural information. The superhero itself works so brilliantly for this because on the surface it’s so juvenile. It’s a character in a costume that fights evil, but at the heart of that is something that’s fantastically challenging, but people often don’t pick it up.

“If you put on a costume and fight crime you are implicitly saying the state doesn’t. This is why you get the reactionary right wing aspect of it, the idea that criminals have overtaken the world. But it also contains the possibility for going off in other directions. If you take this type and you fuse it with strange and unexpected cultural resonances, you get a story that you can’t do anywhere else.”

The forthcoming Doctor Strange might be a blockbuster or a bomb at the box office, and on its fortunes will ride the careers of many a player in Hollywood, not least the man wielding the Wand of Watoomb himself, Benedict Cumberbatch. On the other side of the US, however, in New York City, there will be one man at least, who will view the outcome with a supremely indifferent shrug.

John Naughton writes for GQ Magazine, and covered 40 years of the infamous comic Action for Bigmouth earlier this year.

And there’s more Marvel talk on this archive edition of the weekly Bigmouth podcast. Click to listen now:

Reblogged this on Out of Me Head.

LikeLike

All of the Strange Tales comic book covers in this article featuring Dr. Strange- the #110 and in the slideshow- are not the actual Strange Tales covers. They are awesome fanmade creations by Howard Hallis: http://www.howardhallis.com/doctorstrange/customs.html

LikeLike

Thanks for alerting us, Neil. We’d never have known. We’ve fixed the pictures (see above). Hope you enjoyed the feature all the same. All the best, and may the Vishanti watch over you.

LikeLike

Also, this article implies Ditko drew “The Search”, the double-page image from Doctor Strange #171 that became the famous Third Eye black light poster, but that was after Ditko left. Tom Palmer/Dan Adkins drew that: http://thebristolboard.tumblr.com/post/107324901183/doctor-strange-the-search-a-black-light-poster

And the In-Betweener double-page spread is from Doctor Strange #27. The art of that issue is credited to Tom Sutton. This article in the image caption says Brunner drew it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fixed these too. Sorry for the errors and thanks for letting us know.

LikeLike

This piece and its commentage is an exclesior F.O.O.M moment that I hot diggity dug!

LikeLike

Saw the film yesterday and really enjoyed your article. The movie could have been a bit trippier for me but they get there in places and it was enjoyable, and there is a chunk of Floyd at one point in the film. Steve Ditko gets a proper credit – after Stan Lee of course.

LikeLike

All those cosplayers who are seeking for an inspirational necklace with the exact look, then this are what you need. We have created its copy by using top notch material to provide you nothing, but the exact thing so that you can wear it any Halloween party to compliment your personality. This stylish eye of agamotto time stone necklace is designed very creatively and artistically by our master designers.

LikeLike