The V&A’s latest mega-exhibition You Say You Want A Revolution? promises the last word in ’60s nostalgia… again. But to Paul Du Noyer, a 1960s with only gilded youths and radical-chic celebrities is no 1960s at all.

I.

In 1966 there were two great cultural revolutions getting under way. One was in China, where its figurehead was Chairman Mao and the aim was to purge the nation of lingering capitalist tendencies. The other took place in the affluent west: its unofficial figureheads were probably The Beatles and the aims were various. But getting laid, getting high and having a damned good time were top of most people’s list.

In both revolutions, youth led the charge. China’s Red Guards were paramilitary students who forged a violent upheaval that caused untold havoc and horrific casualties. In the West, there were some campus riots and the odd demo, but our collective memory is of a nice psychedelic wonderland. There were agit-prop trimmings, but hardly anyone died. More people changed their style of trousers than their ideological outlook.

And yet, even in the West, the effect of those years is still felt, and still debated. What really happened in the late 1960s? Was our society deeply transformed in some way? And if so, for better or for worse?

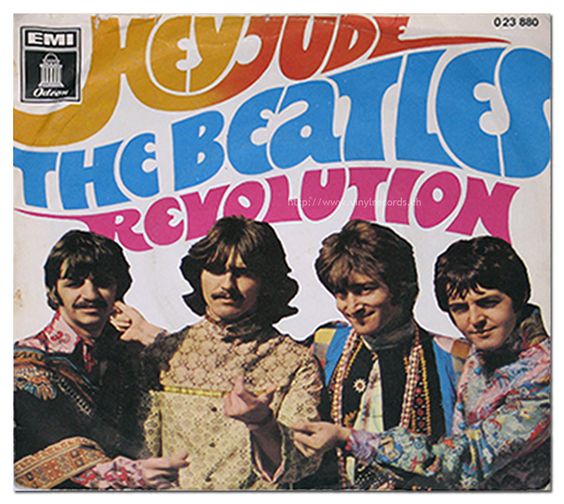

This is where the V&A’s latest blockbuster exhibition comes in. You Say You Want A Revolution? takes its title from The Beatles’ 1968 song ‘Revolution’ and the question mark is important. Did people literally want a revolution? Or just to throw the biggest party in history? Even John Lennon wasn’t sure, and he wrote the bloody song.

Prowl around the show’s club-dark labyrinth and competing ideas will assault your senses via phantasmagorical displays and the Sennheiser head-sets that pump ‘A Whiter Shade Of Pale’ into your brain. Flickering news footage of grim events contends with rock star mannequins and trashed instruments, presented for veneration like icons and holy relics. You gaze at everything from Twiggy’s mini-dress to feminist manifestos to the slick new advertising posters that went up when Madison Avenue decided that grooviness was the way to go.

If nothing else, You Say You Want A Revolution? reveals a period of richly creative confusion.

It does raise another question, though. It nagged at me long before I’d reached that temple of consumerism, the fabulously-stocked gift shop that forms the finale to all modern exhibitions, however radical.

I was wondering about the world this revolution was revolting against.

Back then, I was too young to take part in all the hedonism and idealism have come to define the late 1960s. But I was old enough to take some notice. And what I remember is a world that wasn’t like any of this. It wasn’t like this at all.

- King’s Road, London, late ’60s: Not exactly what the rest of the country is experiencing.

II.

In Chairman Mao’s China, in June 1966, they announced a revolution to abolish “The Four Olds”. By these they meant the old customs, culture, habits and ideas that stood in the way of perfect communism. In Britain, of course, we now tend to remember that summer for The Beatles’ ‘Revolver’ and England winning the World Cup. But here as well, old customs, culture, habits and ideas were being challenged as never before.

For the privileged western young of those years, this was a thrilling new epoch of material abundance and sexual freedom. A generation came of age with no memory of the world war that had shaped their parents’ understanding of life. They had money to spend – not much, by today’s standards, but enough to command a whole leisure economy of their own.

By 1967 a sort of philosophy – or at least an attitude – was arising. It could accommodate everyone from avant-garde poets and frowning intellectuals to the mass teenage market. “Hey hey we’re The Monkees,” sang America’s TV mop-tops. “We’re the young generation, and we’ve got something to say.” The movement’s first catch-word was not revolution but love. “A whole generation,” warbled Scott Mackenzie, in his tuneful hit ‘San Francisco’, “with a new explanation”.

The attitude gathered amazing momentum. It didn’t matter what it meant, exactly. The deal appeared to involve lots of fabulous music in gorgeous gatefold LP sleeves, a certain sense of righteous rebellion, and plenty of beautiful girls in little or no clothing. Somebody had invented The Pill, and there were drugs around that turned the world Technicolor. What (as a later age would learn to say) was not to like?

Soon there was a political dimension, too: the Vietnam War, a nascent civil rights movement, the first stirrings of feminism and gay rights, were all in the mix. By ’68 there was a harder edge to everything, with an appetite for social protest that the Old Left struggled to grasp. Parisian boulevards got torn up by insurgent students, with counterparts across the west from Berkeley to the London School of Economics. The Soviet Union, clearly run by hopeless old squares with short hair, sent its tanks to crush an uprising in Prague.

Coming down from ‘Sgt. Pepper’, John Lennon stopped dreaming of tangerine trees and marmalade skies and wrote ‘Revolution’. Mick Jagger went on a demo and recorded ‘Street Fighting Man’. As soon as pop stars like The Beatles and the Stones were on board, the whole thing became official. They weren’t even “pop stars” any more: they were much more important, like a new caste of hip, lascivious druids.

To any 13-year-old of a certain disposition, the emerging mood was irresistible. In my school-desk I kept a copy of Mao’s Little Red Book.

III.

For a museum named after Victoria and Albert –current stars of a prime-time ITV romantic drama, you may have noticed – the V&A has made a brilliant fist of presenting contemporary pop culture. The Revolution show is in the same suite of rooms vacated by those recent spectaculars devoted to David Bowie and Alexander McQueen. In the pipeline, apparently, is an exhibition about Pink Floyd.

Such a lavish event is expensive to mount, and your ticket will cost £16, even with sponsorship from Levi’s jeans, Fenwick’s department store and the hairdressers Sassoon. There is prominent branding, too, for Sennheiser, whose immersive “sound experience” provides headphones that track your movement through the rooms and play the matching pop song or snippet of period babble. As Austin Powers might say, it’s all son-et-lumière a-go-go, baby.

There is far more here than can be adequately described. But the exhibition’s title will tell you that rock music is the central strand. Film and fashion are strongly represented, as are the graphic arts of posters, underground papers and album covers. LP sleeves from John Peel’s private collection run like a spine throughout the entire display. Wherever you roam, the baleful eyes of Frank Zappa, Pete Townshend or somebody hairy from Jefferson Airplane will be watching you.

- Is that the Roundhouse? Spot the swastika in this indeterminate hippy happening

More than just a multi-media freak-out, though, this was a time of ideas and arguments, of hippies and yippies, locked in perpetual tension between the pleasure principle and purposeful agendas for social change. Much of it looks familiar, even to people who weren’t alive at the time, but you have to get a bit excited at seeing the life-sized ‘Sgt. Pepper’ costumes before your very eyes. And just around the corner will be footage of National Guardsmen baton-charging peaceful demonstrators.

It’s these alternating blasts of hot and cold that make the experience so bracing.

We zoom from Carnaby Street to the Moon, returning to Andy Warhol’s Factory and taking in a few world fairs. (There was still a widespread feeling of optimism about the sci-fi future awaiting us.) The huge room near the end is given over to the Woodstock Festival of 1969, which seems excessive at first. Then you consider that this “tribal gathering” was the point at which the underground went overground. Every climax implies a decline, and Woodstock was a watershed.

The counter-culture was suddenly bigger than anyone had imagined. But where could it go from here? Its followers were growing up, graduating from college, finding themselves with children of their own. How the hell did that happen?

In a way these closing stages, when the 20th century’s most mythologised decade was dwindling to an end, are the most thought-provoking. Just after Woodstock we are played a film collage that lifts a riff from the last scene of the TV series Mad Men. You might recall how it showed Don Draper, the rapacious ad exec, seemingly turn from cynical straight to blissed-out child of Aquarius. The twist is that he is secretly planning to turn that hippy hymn – “I’d like to teach the world to sing, in perfect harmony” – into a new ad campaign for Coca-Cola.

We are stepping, in other words, from a dream of collectivism towards the real-life triumph of consumerism. Hello everybody, meet the 1970s!

Now John Lennon is coming through your Sennheisers again. He’s imagining “there’s no countries”. But of course the multi-national corporations were way ahead of him on that score, and they have the off-shore tax strategies to prove it. Wistfully, we exit the 1960s and are funnelled towards the gift shop.

IV.

Ambivalence is written into You Say You Want A Revolution? from its very title downwards.

As any Beatle-bore will tell you, Lennon released two different versions of ‘Revolution’. One, for the White Album, was a bluesy shuffle that rests upon the soothing line “It’s gonna be all right.” The other, used as a B-side for ‘Hey Jude’, was harsh and clamorous, like a real revolution (though not so uncompromising as another White Album track, ‘Revolution 9’). He sings “count me out”, but then adds “in”.

The exhibition’s signature song is thus fraught with uncertainty. It was typical of John in those years, veering between mystic detachment and clenched-fist sloganeering. Within this one song, he wonders if true revolutions start in the public square or deep inside the human heart. He’d caught the insurrectionary fever that was gripping bourgeois youth, but he could not shrug off his droll scouse scepticism either. He pleads for hard details, which were always elusive in long-haired circles. He teases the Maoist fan-boys with a caution about their sexual prospects.

The popular arts of the late 1960s were full of dazzling innovations, even when they built on ideas that had been brewing for years before. (And, of course, the 1970s were far from arid either.) This was a special time, when political dissent found brilliant expression in mainstream entertainment. It deserves to be celebrated.

But my nagging doubt returns.

You Say You Want A Revolution? is very good, but only its own terms. For such a capacious exhibition, it’s surprisingly narrow in its selection of lives worth considering. I’m reminded of the V&A’s own fashion galleries. They’re fascinating when they show, say, Edwardian evening clothes. But when I look at the 1980s cabinets – a period I was around to witness – what I see are Buffalo Girls and short-trousered men’s suits by Jean-Paul Gaultier. And I think, Hang on, this was only the 1980s if you were a reader of The Face magazine who attended Central Saint Martins art college.

But it’s V&A version, and so it becomes our cultural history.

- British pubs, late 1960s: These people are having a wilder time than Syd Barrett.

What I miss is some information about ordinary life. I’m interested in revolutionaries, but also in the everyday reality that they wanted to revolutionise.

In 1966, I remember people were still flocking to watch The Sound Of Music, which had been out for a year. In 1967, I remember Engelbert Humperdinck keeping ‘Penny Lane’ and ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ off the Number 1 spot with a big fat ballad called ‘Release Me’. When I look at photos from Magical Mystery Tour, I’m always struck by how members of the public look nothing like the psychedelic Beatles. Who were those people, who wanted Julie Andrews instead of Antonioni’s Blow-Up? Who preferred a crooner in a tuxedo to the makers of ‘I Am The Walrus’? Who clambered aboard the Beatle bus in shirts and ties and pullovers?

I wonder about them, and where they fit in, and who tells their story. I wonder about the average dad in 1968. The revolution in his life was finally having his own car to wash on Sunday mornings. If The Who’s ‘Magic Bus’ was drifting out the window from Mum’s transistor radio, well, it was just a funny little song, not an existential challenge.

This other world, meaning the culture that “counter-culture” wanted to topple, is pretty much invisible at the V&A show. An armoured riot cop’s uniform looks stark and brutal, even inside a museum’s glass case, but it doesn’t sum up those people who queued to watch The Sound Of Music.

In 1969 some well-meaning grown-ups opened a youth club in my neighbourhood. They decorated the walls with photos of pop stars, probably from Jackie magazine and certainly not from Oz. In dumb wonderment, I watched skinhead boys reach up to a Fab Four poster and carefully push their cigarette ends through each Beatle’s eyes.

And the music getting played? Thumping US dance anthems like Bob & Earl’s ‘Harlem Shuffle’ or Freda Payne’s ‘Band Of Gold’, echoes of a new Northern Soul scene that music papers didn’t know about. Nobody ever brought in a Captain Beefheart LP. I think I knew who Captain Beefheart was, and I still had my Little Red Book, but I also saw that the whole counter-culture – happening so far away in London and San Francisco – was not the complete picture. It was only one corner of life’s mosaic.

Still, it was the corner I wanted to be in. In time I applied to the London School Of Economics, hoping to find a carnival of glamour and pandemonium. But when I got there, in the early 1970s, that circus had already left town. The students dressed like tramps. I think we had a sit-in, once, but it was called off when the pubs opened.

- Anti-Vietnam war protests in London: Amazing images, but to the rest of Britain it might as well have been Narnia.

V.

The V&A’s curators claim a lot for the influence of their chosen period. Environmentalism, equal rights, even personal computing are all chalked up as part of its legacy. That’s a defensible point of view. But the 1960s counter-culture becomes a sort of magic hat, from which too many rabbits are pulled.

There were millions of unseen, unglamorous toilers, from IBM engineers to female factory workers, who also played their part. One can have enough of solemn Californian greybeards, preaching into video screens, who think they were the first white people to consider black folks as equals. Actually, one can soon have enough of baby boomers’ moral narcissism. There is a photo somewhere of fire-fighters dealing with the aftermath of a riot, doing hard, dangerous, poorly-paid work. But they merit not a mention amidst the gilded youths and radical-chic celebrities.

Not that I blame the curators for concentrating on some sorts of people to the exclusion of others. Civilian populations are not the point of this narrative. Its remit, after all, is the rebels who backed the right causes. Vast social changes may be seeded by small minorities of determined outsiders. Real revolutions are not always the result of spontaneous mass uprisings; they can be made by disciplined factions whose genius is to seize the moment. And then stick around to write the history books.

Civilian populations are not the point of this narrative. Its remit is the rebels who backed the right causes.

Our cultural revolutionaries, in this show, are not so well-organised and almost never armed. Nothing unites the Kings Road dandies with America’s Black Panthers except some thirst for change, ranging from the frivolous to the deadly serious. But all sorts of fresh impulses came into play at the same time, and the commercial fire-power of pop culture – music especially – helped to blast them into our mass-consciousness.

That’s why you meet The Beatles at every turn here. Plenty of their contemporary acts were more “revolutionary” in politics and even in music. But none had their global reach and their ability to popularise ideas for the mainstream. Even The Beatles’ career as a band had some uncanny way of reflecting the counter-culture’s own life-cycle, from poptastic optimism through darker self-doubts and, by decade’s end, bickering disarray.

And what of the foot-soldiers? They were mostly white and middle-class, these peaceful insurrectionaries. It took a certain confidence in your long-term prospects to drop out and live in communes, and a fair amount of leisure time to dream up blueprints for the planet. Mere workers were too busy working.

Since the 1960s, a lot of revolutionaries have found themselves in the happy position of winning both the cultural and the economic wars. They made their peace with capitalism and they prospered. Cool is good, but nothing beats cool and rich.

These are deeper questions than the exhibition can easily cover, but some are explored in the excellent (if pricey) book that comes with it, featuring contributors such as Barry Miles and Jon Savage. If you buy one souvenir from the show, I’d recommend the paperback version of this book.

- The UFO Club, cradle of Pink Floyd

Which brings us out at the gift shop. There is no point labouring the ironies that this Aladdin’s cave presents: hundreds of consumer goodies to round off your thoroughly revolutionary day out in Kensington. Museums must pay their way and the V&A does it with some panache. No doubt the thronging visitors will include a fair contingent from China, whose own cultural revolution has been officially disowned, just as their rulers have now embraced capitalism.

They can then take home their Levi jeans, tarot cards and Jimi Hendrix audiophile vinyl, and talk about this other revolution, that happened in the western world fifty years ago. And has not stopped happening since.

The curators suggest, actually, that the counter-culture encouraged a growing acceptance of neo-liberalism. People absorbed the fashionable ideas like self-expression, self-actualisation and self-fulfilment. And they decided it was the “self” bit they liked best.

Even the quest for karmic harmony was apt to get re-packaged in sales-friendly forms. Out went the garden gnomes of suburbia, and in came plaster statuettes of Buddha. (“I’m spiritual, but not religious.”) IBM are still trading, but the modern computer giants are run by men in T-shirts, not Brooks Brothers suits.

If you’d told people in 1972 that they’d one day travel in trains run by the beardy raver who owned Virgin Records’ head shops, they would have laughed.

Well, they’re not laughing now.

You Say You Want A Revolution? Records And Rebels 1966-1970 is at the V&A in London until Sunday, 26 February 2017

Hear Paul du Noyer on Philip Norman’s Paul McCartney biography in this edition of our weekly pop culture podcast:

The Souper Dress © Kerry Taylor Auctions 1966. Anti-Vietnam demonstrators at the Pentagon by Bernie Boston, The Washington Post via Getty Images. 1967. John Sebastian performing at Woodstock © Henry Diltz Corbis 1969. Poster for the Family Planning Association, Cramer Saatchi Advertising Agency. 1969 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Blow Up, 1966 © MGM The Kobal Collection. Poster for The Crazy World of Arthur Brown at UFO, 16/23 June, by Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, 1967. Acid Test poster designed by Wes Wilson, courtesy of Steward Brand, 1966.

I grew up during the middle/late 60s (18 in 1966) and it is true that the ‘cultural revolution’ impinged very little on the lives of the vast majority of people. The ‘scene’ in London at least involved several hundreds, maybe a thousand or two people at most, and even then was concentrated in areas such as South Ken, Notting Hill, Earls Court, Camden. If you looked at all hippieish you had to be careful going out if you lived in East London or Docklands (as I did).

The difference, however, is that the influences of the 60s filtered through gradually. At a trivial level, just look at photos of football crowds in the early 70s – long hair, sideburns, even flares. Clothes and cinema were other areas where the 60s influence was delayed but pervasive. There is a lot of truth in the view that the 60s actually happened in the 70s. I would argue that the pop culture of the 60s had a more far-reaching effect on the wider population, over time, than later explosions such as punk or the New Romantics.

LikeLike